In true measure |

|

| Colm Carey on why marketers ought to put advertising measurement in perspective |

Some of the hottest debates in adland are based around evaluating the success or otherwise of an ad. There is an industry built around measuring advertising effectiveness and lots of money is spent searching for the holy grail of sure success.

Whether you are advertising a clear out of flat screen TVs or trying to build a multinational brand franchise, the question of return on investment arises each time and you have to justify the cost of advertising.

At the start of the last century, advertising effectiveness measurement was based on evaluating the impact of direct response newspaper advertising. You put an ad in the paper and measured success by the number of people who called to your store.

It led to a belief that advertising worked on the basis of awareness, interest, desire and action. The AIDA acronym is still in use in marketing today and it relies on generating conscious awareness as its core principle.

Awareness can be easily measured when you define it as a purely conscious process.

Conscious awareness is evaluated by measuring recall. Since awareness and recall are the presumed precursors to interest, desire and action it thereby follows, that the higher the attention and recall, the more effective the advertising.

Based on this credo, methods were devised to measure awareness and recall. Research involved with its norms and statistical tools gave the process scientific validity. When radio, TV and digital came along the existing tools were used to measure their affect.

Much of the appeal of the awareness and recall model of advertising evaluation lies in the fact that the process provides hard data. Clients feel comfortable with hard data. Share price, last quarter sales, next quarter projections, earnings ratios and return on investment, are the language of the corporate world.

Careers and companies rise and fall based on hard data.

Soft data tend to make corporate organisations uncomfortable but as people a lot of our decisions are based on soft data involving emotion and intuition – the right side of the brain.

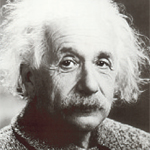

Add to the mix the fact that major research companies and their clients have invested a lot of time and money in methodologies that primarily measure awareness and recall and you have a potent argument for retaining the status quo. But we need look no further than Albert Einstein to find a reason to apply the brakes.

Einstein said that not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts. The maxim is a warning to us all when we get caught up seeking comfort in pure numbers, rather than taking account of emotion and intuition.

Exploring the history of advertising measurement helps to explain why the original scenario in which the advertising was subject and the research was object sometimes becomes inverted. It seems the research is the subject and the advertising the object.

The greatest danger in adopting this paradigm either consciously or unconsciously is that you start creating advertising designed to perform well on whatever tool your company uses to measure success. It can prove to be a narrow gauge.

The 1950s saw the birth of the unique selling proposition. Its arrival meant that as well as being recalled an ad now had to plant a suggestion in the consumer's brain that triggers an urge to buy the brand. A simple but clever line was considered the best vehicle for your USP so measuring the recall of copy became part of the equation. The new dispensation drifted into advertising with the growth of qualitative research. Issues of emotion, the unconscious and psychological theory entered the equation but awareness and recall continued to be the main criteria for advertising success.

The launch of a more holistic approach to measuring ads struggled because the dominant research methodologies focused on measuring rational responses. The situation is much the same today despite the efforts of experts like Robert Heath, Paul Feldwick and John Howard Spink, who exhort advertisers to stop focusing on how to get attention and instead create meaningful relationships with consumers.

Brands that have focused on working to create relationships rather than simply get attention include Bulmers Cider and Barry's Tea, each of which has become an iconic Irish brand seeking more than awareness and recall in its advertising.

We remember ads that touch us emotionally years after they have finished their tour of duty. We forget ads that scream for awareness as soon as they leave the building.

At a time when people are looking increasingly to find meaning and positive emotional values in their lives, it makes sense to spend your advertising money touching the chords that generate a deep and positive emotional response, rather than engaging in what is often meaningless, attention-seeking behaviour.

|

WISE WORDSAlbert Einstein once said that not everything that counts can be counted and not everything that can be counted counts, a maxim that could apply to advertising. |

Colm Carey (colm@theresearchcentre.com) is a psychologist and qualitative researcher